In the preface to the 2006 edition of Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, Ligon Duncan has a most telling comment.

Pagan ideas underlie evangelical egalitarianism, based, as it is, on ideas borrowed from cultural feminism. Egalitarianism must always lead to an eventual denial of the gospel. When the biblical distinctions of male and female are denied, Christian discipleship is irretrievably damaged because there can be no talk of cultivating distinctively masculine or feminine virtue. One can only speak of vague androgynous discipleship. But that’s not how God made us. We need masculine males and feminine females in order to generate the kind of discipleship that results in a commitment to complementarianism. XII

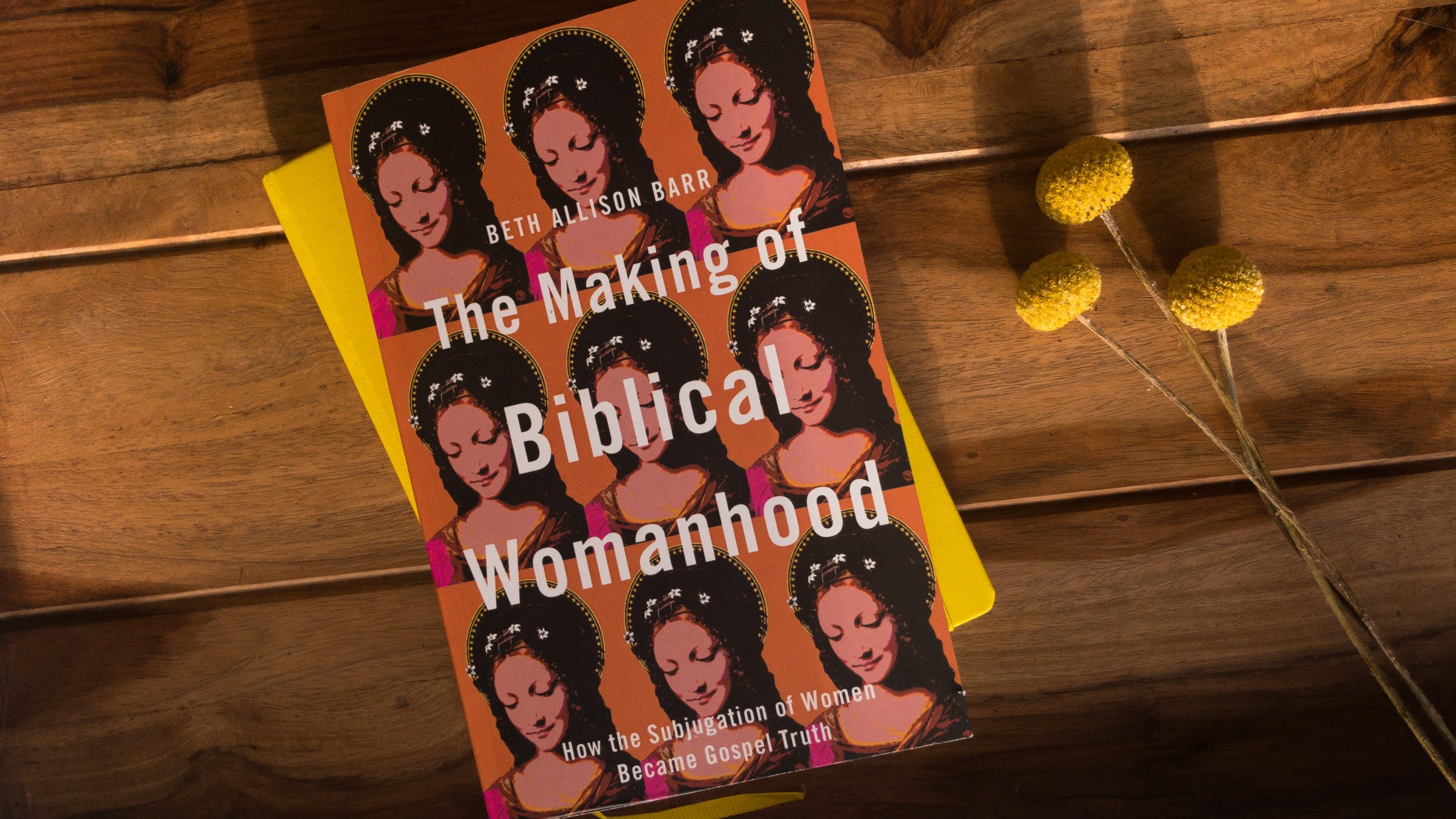

There is plenty we could unpack from this quote, but a couple of things need special mention. The first claim, egalitarian theology is derived from a pagan culture, while complementarian is not. And the second resultant implication, egalitarian theology undermines the entirety of the gospel. The first claim that the pagan or secular root of egalitarian theology and the biblical foundation for complementarian theology or biblical manhood and womanhood (BM&W) is one of the most common claims when approaching gender issues today. In her forthcoming book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood, Beth Allison Barr uses her expertise as a historian to look at this and other claims to see how this ideology made it to where it is today. Her answer will find that overall these are empty claims. I want to work through her book sequentially, offering both summary and comment. (Two preliminary comments are needed. 1) I received an advanced reader copy from BrazosPress 2) Because of that my page numbers may not reflect the final product- I will update as needed)

She first looks at the foundation of biblical womanhood and shows, convincingly, not only that complementarianism is patriarchy (13) but that Christian patriarchy models mainstream historic patriarchy (19). The implications she then develops turns many of the arguments, like the aforementioned Duncan one, on their head. Specifically, this is that BM&W is not the Christian response to pagan ideology but the logical continuation from it. The apparent qualification that Christian patriarchy is different because it only requires a woman to be under the authority of her own husband and her male pastor doesn’t hold water when looking at how it plays out in reality. Barr recounts how a male student suggested that she, with an earned doctorate, clear her material with her husband before presenting it. This student, she concludes, couldn’t accept that a woman, he believed was under the authority of a man, could have authority over him (17). The wake of patriarchy is long and deep. She then traces its origin through the epic of Gilgamesh to now, further supporting these claims. She then concludes by echoing Sarah Bessey that patriarchy is not “God’s dream for humanity” (37).

Barr will then turn to Paul, whose words are often used as a sledgehammer to keep women where patriarchal men want them. But like many before her, Barr is convinced the Paul is not the culprit, but poor reading and patriarchal reception history has formed him into one. Barr does her own demolition of this framework and finds a counter-cultural Paul, opening up space for women to freely serve Jesus as partners with him. Barr reminds us that you cannot silence Paul’s women.

From here, Barr finds her legs as she surveys the medieval and reformation periods. She recounts story after story of women who stood out, defied the norms, found a way and were accepted as preachers and teachers. But she also reveals more of the grip that secular patriarchy still had on the church. This she argues was heightened in the post-reformation era. This is because a married mother became the ideal Christian woman. Moreover, she would be defined by her relationship with her male relative. The post-reformation women were not able to define their own narrative, they were at best, supporting actresses, at worst an uncredited extra, in a film written by, directed, produced and starring their husbands.

This sets the stage for some of the more controversial chapters, commencing with how interpretive and translation bias has stacked the deck against women in our English Bibles. Barr reminds us that “translations matter’ and the matters of translation have skewed the data. Over the past 20-30 years gender-inclusive has become almost a curse word for complementarians. This has led to a renewed interest in ‘brothers’ instead of ‘brothers and sisters,’ ‘man’ instead of ‘humanity’ and ‘fathers’ instead of ‘ancestors.’ But Barr’s comments go beyond this and even before this. She again allows history to be a witness and find gender-inclusive terminology was prevalent among Medieval clergy and writings, even using it to better care for people pastorally (143). But something changed, what was it? Barr suggests the world did. Bias exists everywhere, biblical translation and editing included. Barr highlights how what can be described as a patriarchal bias seemingly influenced biblical translations from the KJV to the ESV. The KJV is still hugely influential today, even with its archaic language and manuscript questions. What this means is that for many people, a patriarchal reading is the default one. So when the NRSV or TNIV offered a ‘new’ option leaning towards inclusive language, they were swimming upstream, regardless of if they were offering a better or more faithful reading. Looking at the ESV, a recent study by Samuel Perry shows how its editors explicitly forced patriarchal theology into their decisions. Barr does not address all of these elements but instead gives examples of some of these actions in practice. Such as a 17th-century preacher using ‘false universal language’ to exclude women or how masculine pronouns can be added to a text to emphasize maleness that isn’t necessarily there (147-8).

Before I continue, I need to offer a brief aside. There are comments about this section, and the one about Paul, criticizing Barr for not doing much exegetical work, as she does not do much. I find these comments to be misdirection meant to change where the battle is being fought. Barr is a historian (Medieval), if she didn’t tell us that, it would be obvious by her work in this book. Without pushing any false dichotomies, the goal of this book is to look at the historic development of BM&W. Yes, there are biblical exegetical implications here but that is secondary to the stated goal. Moreover, the arguments for passages such as 1 Tim 2 from both sides are well known and accessible to those who might be interested in finding them. Barr also offers numerous endnotes to sources who make some of these arguments. What I think those critiquing her on this are trying to do, is to dismiss her historical framework with a naive appeal that says she isn’t biblical enough. Why? Because then they can just say ‘see, the plain reading of the Bible says this’ and ignore her implications. Is this a cynical take, maybe, but I have spent enough time in complementarian settings that do this almost unapologetically. Debates are won and lost in the definition of terms so if you can’t defeat the argument itself, change the definition of terms.

Barr’s next chapter deals with purity culture and the idol of the domesticated wife. How and why did that come about. It is an important chapter but one I am going to leave aside for now. I plan on dealing with purity culture on its own and this chapter will be addressed then. Her theme continues, this was not how it had always been and its source seems external from theology rather than internal.

This sets the stage for a final chapter before she calls us all to action. This one synthesizes so much of what was offered before but looking at how in the last few decades everything came together to cement BM&W into gospel truth or as she says “to write female submission into the heart of Christianity” (174). How did this come about? I guess you could say the usual way. First, history is forgotten. Barr shows numerous examples of women in public ministry throughout the ages, including in the Southern Baptist Church. In contrast to the claims of Grudem and Piper that this would cause “the withdrawal of God’s hand of protection and blessing,” Barr following Timothy Larsen shows the opposite is true. On a whole, churches that support women in ministry, defined as service to adult believers, “are most closely aligned with the gospel of Jesus” (178-179). She continues that because modern evangelicals only know a sliver of their history, they lack the data to evaluate the claims of Piper, Grudem et al and are left to merely accept what they say. After a re-telling of history, holiness came to be redefined. A good and godly woman was a passive stationary vessel, in contrast to the active fleet-footed male who spread the good news of Jesus (185). The active woman was in danger of undermining men’s authority- male fragility has a long history.

But holiness was not the only thing redefined, orthodoxy itself was changed. Suddenly inerrancy became the litmus test of Christian faithfulness. If you rejected inerrancy as defined by the Chicago Statement, you called into question the veracity of everything within the biblical text. On the flip side, if you suggested the apparent plain and literal meaning of 1 Timothy 2 might now actually be what we think it is, you were arguing with scripture and thus God himself. Permitting women in ministry was just a slippery slope to liberalism or heresy they argued. Ironically, it was some of the main proponents of BM&W who ended up in heretical hot water, as they tried to undergird their arguments for female submission in the eternal submission of Jesus to the Father. Barr rightly points out that this line of reason slips into Arianism, contradicting the creeds and out of step with Christian orthodoxy. Over the last few years, there has been much discussion on this and apparently, the eternal submission of the Jesus crowd have modified their views but the trickle-down effect is still going on. It is fascinating that BM&W proponents like Grudem would be comfortable with heresy just to keep women in line.

This chapter is hugely important and Barr emphasizes why this is true as she wraps it up. In the minds of many leading complementarian thinkers, this is almost a gospel issue. The Ligon Duncan quote in my first paragraph is one example. Barr adds her own from the Gospel Coalition and its key leaders Tim Keller and John Piper. They include it in their statement of faith. And a denial of BM&W loosens our understanding of scripture (199). There is no room for compromise, no room for discussion because the gospel is at stake here. Barr captures this with a tongue-in-cheek concluding line “No wonder we were fired. We were dangerous to the gospel of Christ” (200).

In her concluding chapter, Barr shows why this is so serious and why we need to finally truly set women free. Barr tells her #MeToo story, one that we have heard over and over again with slightly different players. Sadly so many of these stories also have to say #ChurchToo. For some reason, there is an apparent disproportionate correlation between BM&W and abuse. The Houston Chronicle did an exposé that found some 700 victims over 20 years connected with Southern Baptist Churches. Recent books by Ruth Tucker (Black and White Bible, Black and Blue Wife), Aimee Byrd (Recovering from Biblical Manhood & Womanhood), and Kristen Kobes Du Mez (Jesus and John Wayne) have all shown certain complicity between patriarchy and abuse. Barr wants us to be better and we must be better. Moreover, if her argument is correct then Christian patriarchy is rooted in secular paganism and so much of what we assume to be Christian is rooted in other sources and must be released from Christian thought. I think she is correct and thus the time for patriarchy to have any meaningful place in Christianity to be over.

I believe this book needs to be read and considered. It has a compelling argument but it is also personal for her, as she reveals much of her and her families story in it. That is risky. I hope that many will give her arguments an honest look and be willing to rethink their understanding of biblical personhood because of it. I think of complementarian pastors who have a bad taste in their mouth waiting for someone to nudge them to rethink their view about women in church leadership- Barr can be that nudge. I also think of women, in marriages that are from the biblical ideal, who stay silent because their church tells them it is the proper way, who might find their voice through Barr. This is why this book matters because it offers a better vision of personhood, rooted in Christian history, theology, and the biblical text itself.